Firma

Productividad

Desarrollo

Código Abierto

3 feb 2026

If you’ve ever set up an envelope in Documenso or any document signing application for a real-world document (employment offer, rental agreement, sales contract…), you know the most difficult part usually isn’t sending the link. It’s the setup.

You upload a PDF, then you:

add recipients (sometimes more than you expected),

search through pages for different signature lines, sometimes missing some,

drop fields in the right places,

assign each field to the right person, getting it wrong means sending another document,

and try not to miss that “Date” box hiding on page 9.

That setup is repetitive and error-prone and it could be made easier. We just shipped a new “AI features” layer on top of Documenso’s envelopes: automatic recipient detection and field detection for uploaded PDFs, shown in the editor as “Detect with AI” just to solve this issue.

At a high level:

When you upload a document and go to the Recipients step, we can scan the PDF and propose who should sign (names, emails, roles).

When you move on to the Fields step, we can scan the pages and propose where the signature, date, text and other fields should go.

Everything is optional, reviewable, and gated behind explicit organisation/team settings and infrastructure configuration.

This post walks through what we built, why we built it, and how it works under the hood.

Constraints

We had a few non-negotiables:

Privacy. Document contents are sensitive. Any AI integration must be explicit, opt-in, and deployed in a way that’s compatible with enterprise expectations (data residency, training restrictions).

Predictable results. A free-form AI response is hard to trust, outputs vary from time to time even with the same prompt. We need structured output that our backend can validate.

Fast. Field detection and recipient detection can take multiple seconds, especially on multi-page PDFs. We didn’t want a single long request that looks frozen, times out, or gives no user feedback.

Design choices

We had to make some choices for our non-negotiables.

Privacy: We chose Gemini on Vertex AI and wired it through Vertex AI in express mode / API-key auth, because it simplifies setup. Google Cloud’s enterprise generative AI posture includes statements that customer data isn’t used to train models without permission.

Predictable results. Instead of asking the model to return text (“I found 7 fields on page 2…”), we generate structured outputs that match a schema and validate it server-side. We use the Vercel AI SDK’s

generateObjectpattern: “here’s a schema; generate an object that matches it.”Fast. The server streams updates as NDJSON. NDJSON is dead simple: each line is a JSON object; clients can parse the stream line-by-line. It’s faster and doesn’t make the editor look frozen.

Design overview

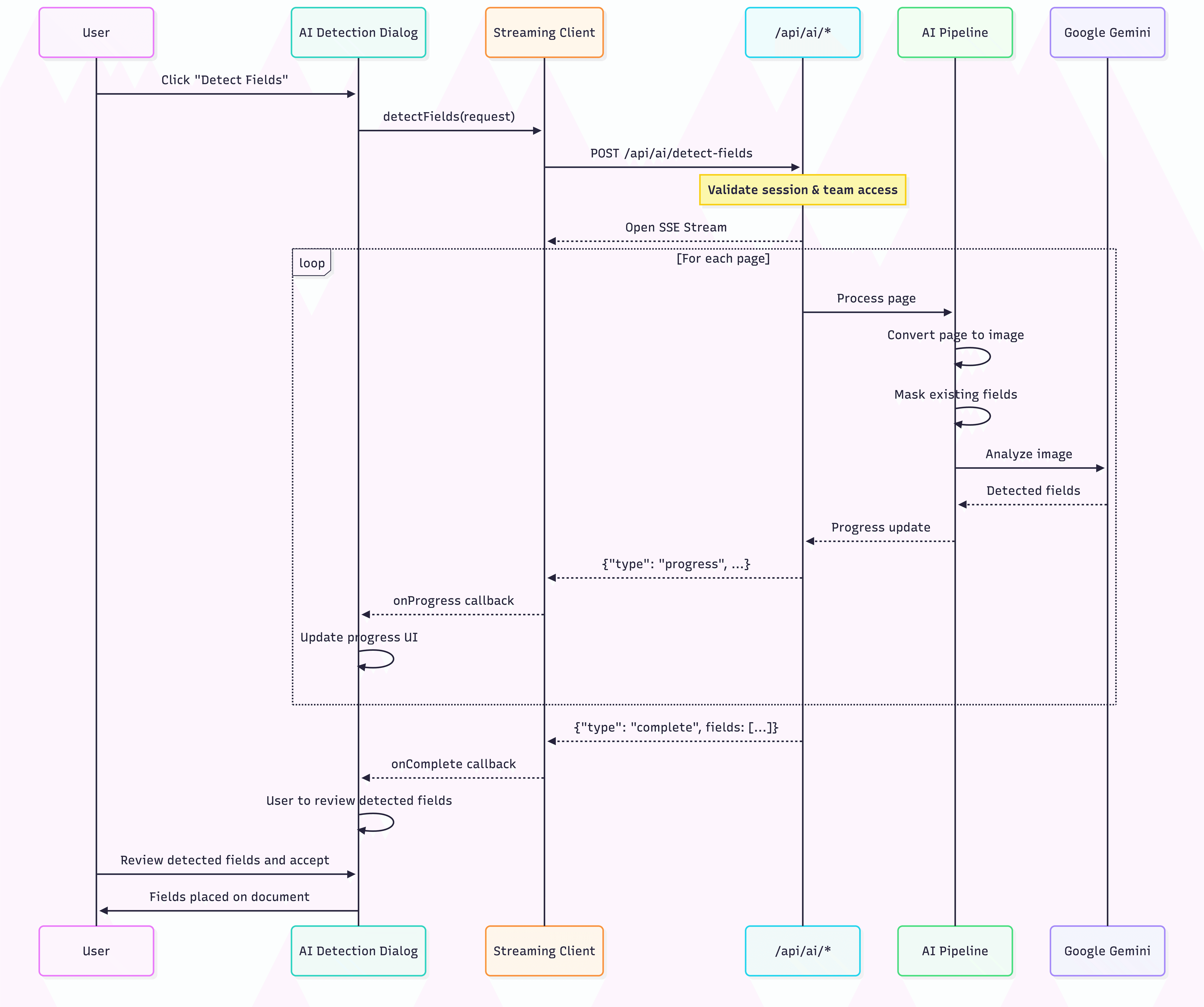

The user starts detection from the document editor, the client opens a streaming connection to the backend, and the backend processes the document page‑by‑page through Vertex and returns field objects with bounding boxes. Instead of making the user wait for an entire document to finish, we stream progress updates as each page is analyzed, then return a single “complete” payload containing all detected fields. The editor then renders those bounding boxes immediately for review, giving the user the final say before anything is permanently placed on the document.

The sequence diagram below shows the complete end-to-end flow, starting from the user’s click in the UI, through the streaming API layer, into the page processing pipeline that converts pages to images and masks existing fields, and finally to the Gemini analysis step that produces detected field objects. It also highlights the feedback loop: progress events are pushed back as NDJSON so the UI can continuously update status while the pipeline runs, and the final result is returned as a structured list of fields ready to render and accept.

Turning PDFs into images

Large language models can work with both text and images, but real‑world PDFs are messy: they might be scanned, contain weird text encoding, or mix vector text and images. Instead of trying to parse the PDF’s internal structure, we render each page to an image and let the model “see” the page like a human would.

We turn the PDFs into images with pdf.js and a server‑side canvas implementation:

pdf.jsis the standard open‑source library for rendering PDFs into a<canvas>element.On the server, you can use pdf.js with a headless canvas library (like

skia-canvas) so thatpdf.jscan draw without a browser.

For each page we: ask pdf.js for the page viewport at a fixed scale, create a canvas of that size, let pdf.js draw the current page onto the canvas and then encode the canvas as a JPEG buffer. These images and the dimensions of the images are the backbone for the next step, where we ask the model to output bounding boxes for empty fields.

Mask existing fields

Before we detect the fields and recipients, the first thing is to mask (hide) the already existing fields. This is one of those small implementation details that changes the entire feel of the feature. Instead of running detection and then trying to merge/dedupe results, we “pre-dedupe” visually by painting over already-known fields.

Here’s the essence (shortened) of what we do:

This works well because our existing fields already live in Documenso’s normalized coordinate space. Converting the already existing fields to pixel rectangles on the rendered image is deterministic. The model doesn’t need to understand “this is an existing field.” It just needs a simple rule: ignore black rectangles.

Structured outputs

When the fields are masked, we detect the remaining fields. We do this the same way for recipients: ask for an object that matches a schema, then validate it. If it does not match, we throw it away.

Recipients schema:

Fields schema highlights:

The types we accept match what the editor can render: SIGNATURE, INITIALS, NAME, EMAIL, DATE, TEXT, NUMBER, RADIO, CHECKBOX. Confidence is a simple enum from low to high. The core detection call uses schema-constrained generation with Gemini 3 Flash:

We never parse prose. If it does not match the schema, it does not ship.

Field detection: field types and bounding boxes

This is the part that made the feature actually usable: bounding boxes that line up with our field model, every time. We already store field positions as percentages (0-100) in Documenso. So we made the model speak a coordinate system we can map to that world cleanly. The flow looks like this:

Render each PDF page to an image (pdf.js + skia-canvas).

Paint over existing fields as black rectangles so the model ignores them.

Resize the image to 1000x1000.

Ask for

box2din a 0-1000 grid.Convert

box2dto our 0-100 percent positions.

That last conversion is tiny, but it is the trick:

Because everything is normalized, a signature line on an A4 page and one on a US Letter page end up in the same coordinate system. The editor can render them without caring about the original pixel size.

We also pushed a lot of "what does a field look like?" logic into the prompt. For line-based fields we ask the model to expand the box upward into empty space so there is room to sign or write. We also set minimum sizes so you do not end up with a 2-pixel-tall box. And we tell it, repeatedly, to exclude labels and only box the empty area. That is what makes the overlays feel right when you drop them into the editor.

One more detail I really like: recipient assignment happens here too. We build a recipientKey list that looks like id|name|email, pass it to the model, and ask it to use those keys when a field label implies ownership ("Tenant Signature", "Landlord", etc.). On the way back we resolve the key to a real recipient. If the model punts, we default to the first recipient so the field is not orphaned.

Recipient detection

Recipient detection is a similar loop, but with different trade-offs. Instead of per-page calls, we batch pages in chunks of 10. That is small enough for the model to keep context, but big enough to avoid a ton of round trips.

We also keep the running list of recipients and feed it back into the prompt on each chunk, which helps reduce duplicates. After each chunk we merge new candidates by email or name, so "Jane Smith" only shows up once even if she appears on multiple pages.

The schema is intentionally forgiving: name and email can be empty if the document does not include them. We only set a role if the language makes it clear (SIGNER, APPROVER, CC, VIEWER), and we default to SIGNER when it is ambiguous. The goal is a solid first pass the user can edit.

Streaming with Hono

On the backend, both AI endpoints are Hono routes that stream NDJSON. Each line is a JSON event:

progresswith pages processed and how many items we have seencompletewith the final payloaderrorif something breakskeepaliveevery 5s to keep the connection open

Hono's streamText makes this clean. We write one JSON object per line, flush it, and the client can parse the stream incrementally. On the frontend we use fetch, read the ReadableStream, split on newlines, and run each event through a Zod discriminated union before we act on it. That gives us type-safe streaming with a tiny amount of code, and it keeps the UI responsive even on long documents.

Conclusion

The high-level idea is simple: turn PDFs into images, ask Gemini 3 Flash for structured output, and stream the results as we go. The parts that made it work in practice were the boring ones: a single normalized coordinate system, masking existing fields, and strict schemas. Those details kept the UI honest and made the results predictable enough that people actually trust them.

We are still conservative about this feature. It is always opt-in, and every detected field or recipient is just a suggestion. But it now takes most envelopes from "blank page" to "almost done" in a few seconds, which is the exact kind of help people want.